A Munitions Plant for 3 Wars (Plus a Cold One)

By Mary Gavin

October 29, 2025

View of the remains of the munitions plant at Newport, Ind. Photo by Larry Gavin

What is now Vermillion Rise had several other names when it was operated under the auspices of the United States Army – Wabash River Ordnance Works, Newport Chemical Plant, Newport Chemical Depot, Dana Heavy Water Plant, Newport Army Ammunition Plant and Newport Chemical Agent Disposal Facility.

But to most local residents, the area just south of Newport, east of Dana and west of Hillsdale, Ind., was known as the plant. Through decades of war and external threats, this relatively small area in the midst of Indiana agriculture was a munitions factory

Commissioned by the Army in 1941 and built the next year, it was the site for the production of weapons of war: the explosives RDX and TNT, heavy water for the Manhattan Project that developed the atomic bomb, and the nerve agent VX.

For more than two decades, the destructive power of these materials helped the United States prevail against its enemies. The Army offered steady and patriotic employment work to many who lived nearby.

In wartime, there seemed to be an implicit tradeoff: the destruction of land, buildings and people on other continents in exchange for preserving this country and its freedoms. The damage wrought on the land may have seemed negligible in comparison to the threat posed by the then-current enemy. Only decades later was the fallout of the manufacturing and disposal of the weapons acknowledged and steps taken toward remediation.

The weapons are gone now, some used in warfare, remnants destroyed. Now only 6,665.2 acres, with 108 buildings, woods, fields where farming has continued for the most part uninterrupted, and at least one cemetery remain. The place is now the industrial park Vermillion Rise devoted to attracting businesses to the area.

RDX: RX for Britain

After the fall of France in 1940, President Franklin Roosevelt had begun to prepare the United States country for the war that, at that time, very few wanted. But the bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941, brought the country into World War II, and in early 1942, work on the plant began.

Newport, Vermillion County, Indiana, in the heart of rural America, seemed a good place to develop a plant for explosives. It was the requisite 200+ miles from coastal waters and international borders, and there was plenty of water, electric power, and available labor. In 1941 the federal government acquired more than 22,000 acres for the Wabash River Ordnance Works, which included farmland, homes, a church and six cemeteries.

Within about seven months – Jan. 2-July 20, 1942 – E. I. DuPont de Nemours & Co. built the Wabash River Ordinance Works, (WROW) to manufacture Royal Demolitions Explosives, or Research Development Explosives – by either name, RDX, at that time the most powerful explosive known.

The British were manufacturing RDX but their needs outpaced their supply.

RDX plant at the Wabash River Ordnance Works, 1942. Photo provided by courtesy of Indiana State University Library

Aerial view of the RDX plant. Credit: GlobalSecurity. org

Although in 1941, chemists at The University of Michigan had discovered a way to make RDX more efficiently than the British, that method was not used at Newport. In light of the immediate need for RDX, the plant was designed to use the slower method, and WROW manufactured only a fraction of the RDX produced nationwide.

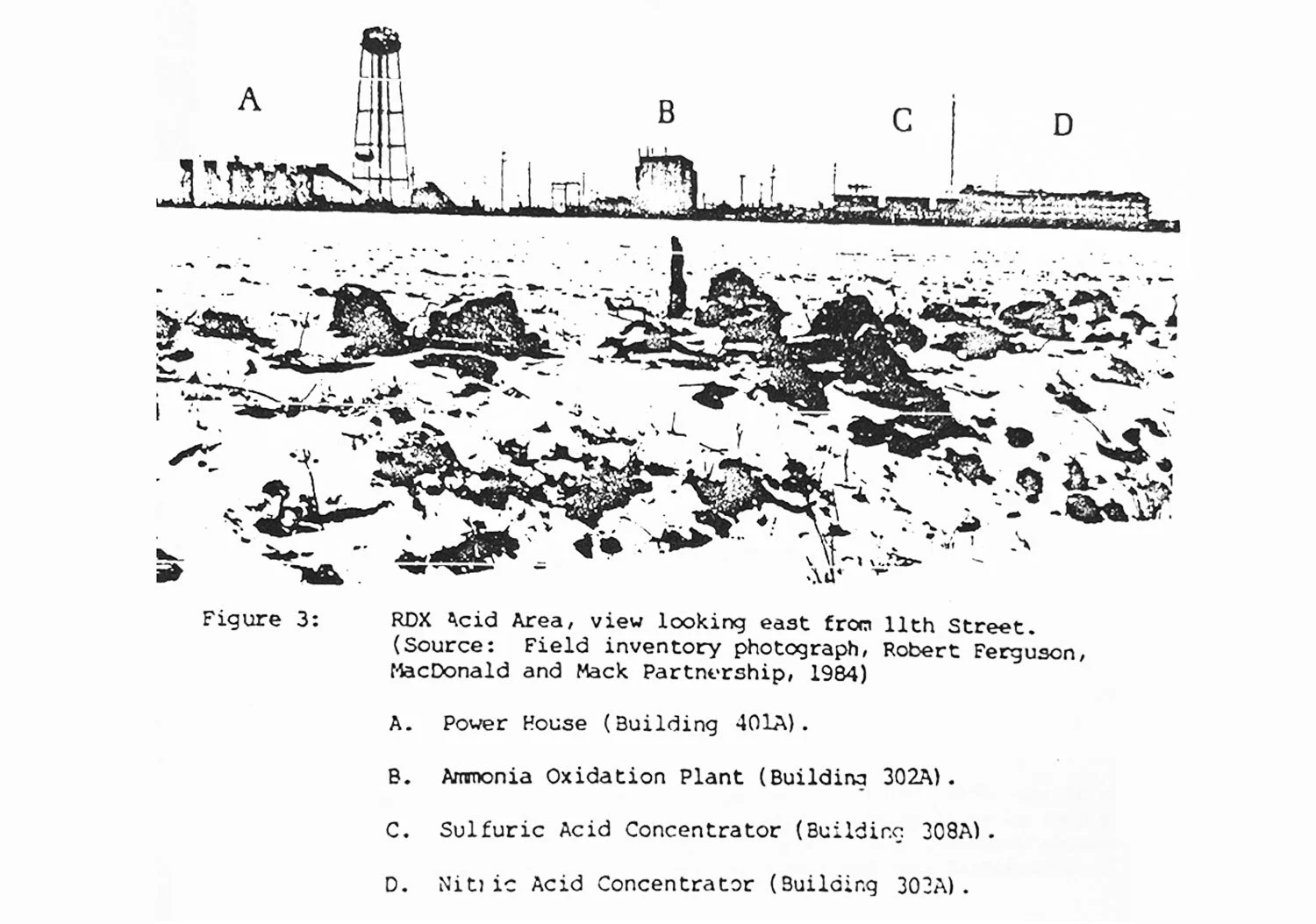

Figure 3 from the historic properties report

Because the manufacture of RDX required highly concentrated nitric acid, the plant at Newport “used the time-honored technique of concentrating the 60% nitric acid by dehydrating it with sulfuric acid,” according to the Army’s Historic Properties Report. “The spent sulfuric acid, now diluted with water, was collected in concentrator drums at Building 308A, where it was dehydrated by blasts of hot gases from oil-fired furnaces. The reconcentrated sulfuric acid was then ready to be recycled in the nitric acid operation.” Information and image from the Historic Properties Report: Newport Army Ammunition Plant.

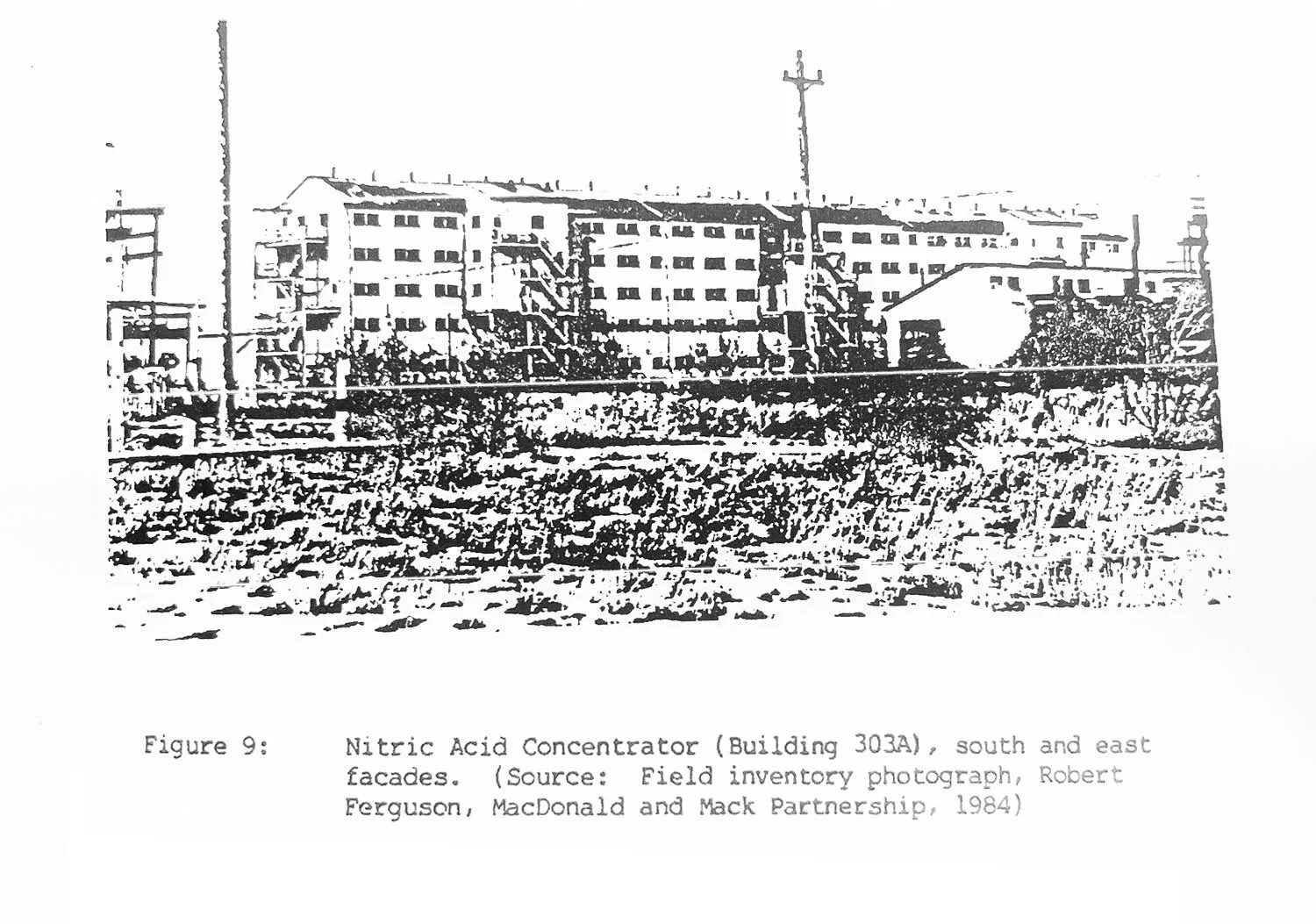

Images from the Historic Properties Report: Newport Army Ammunition Plant.

“The Bomb that went off twice,” a special report to Pro Publica published on Dec. 18, 2017 by Abraham Lustgarten, said, “RDX enabled the bazooka — the world’s first hand-held anti-tank rocket launcher — to pierce armor. RDX was packed into 10,000-pound underwater bombs dropped by British airplanes to blow up German river dams and disrupt the country’s hydropower in the critical Dambuster campaign. It was even surreptitiously soaked into firewood that would later explode in the furnaces of German locomotives.”

Not only did RDX play a large part in the Allied victory in World War II, it also, Mr. Lustgarten wrote, “fueled the vast carpet bombing of the Korean peninsula, and then later, America’s involvement in Vietnam.”

While a significant amount of RDX was manufactured at WROW in Newport, most of this powerful explosive was made in the Holston Plant near Kingsport, Tenn.

D2O: The Manhattan Project and the Korean Conflict

In August of 1942, the Chief of the United States Army Corps of Engineers formally established the Development of Substitute Materials. Led by the United States, the project involved the United Kingdom and Canada in the pursuit of developing nuclear weapons before Nazi Germany could do so.

Based initially in Manhattan, it was soon called the Manhattan Project, though the central location was Los Alamos, New Mexico. Scientists from Clinton, Tenn. (near Knoxville); Hanford, Wash.; Chicago – and even Newport were involved.

In less than a year – Jan. 23-Dec. 13, 1943 – DuPont added a discrete, and discreet, facility at WROW, called the Dana Heavy Water Plant. It produced deuterium oxide, or heavy water, for the Manhattan Project’s creation of the atomic bomb.

Heavy water was produced for the Manhattan Project at a separate area of the plant, called the Dana Heavy Water Plant. Photo courtesy of Indiana State University Library

The Atomic Heritage Foundation notes on its website, “For security reasons, the plants had to be administered directly by Manhattan Project officials while the Ordnance Department was, according to Colonel James Marshall, ‘not to be involved in the design or knowledge of use of the product.’”

Applied to uranium (U-238), heavy water allows it to undergo fission. This is the process the Germans were pursing during World War II.

Heavy water occurs naturally but rarely – only one water molecule out of every 4,000-20,000 will be deuterium. Because deuterium is so rare naturally, electrolysis or distillation were the processes used to separate heavy water from regular water.

However, in 1943, a process to create heavy water by adding a second neutron to a hydrogen atom through an isotopic exchange, made it twice as heavy (deuterium). The process was named after the Girdler Company, which built the first large-scale plant using this process; another name for the process, the Geir-Spevack Process, acknowledges the inventors.

This was the process used at the Dana plant.

Manufacturing heavy water required massive amounts of water, for cooling as well as for the process itself. Although there is no precise estimate, a former CEO of Vermillion Rise said the Dana Plant used about 1 million gallons of water per day.

After the end of World War II, in 1946, the manufacture of heavy water ceased. But in 1951, nuclear weapons were back on the scene. After the United States entered the Korean War, Du Pont resumed production at the Dana Heavy Water Plant, as the United States carried out its nuclear weapons program for the next five years.

The military also needed RDX for the war effort in Korea. Liberty Power Defense Corporation of East Alton, Ill., a subsidiary of the Olin Corporation, reinstated two of the five RDX lines there to make explosives for the Korean War. Liberty operated the plant under contract with the U.S. Army from August 1951 until March 1957.

TNT for Vietnam

TNT was manufactured at the Newport plant for use in

the Vietnam conflict. The five lines for production were designed by Du Pont. Image provided courtesy of Indiana State University Library

Munitions continued to flow from the plant. During the Vietnam conflict, from 1968 to 1973, Du Pont designed five lines for the production of TNT.

One of the most widely used military explosives, TNT is made by combining toluene with a mixture of nitric acid and sulfuric acid. TNT is yellow and odorless and remains a crystalline solid at room temperature. It was used in military cartridge casings, bombs and grenades and likely played a large part in the U.S.’s Operation Rolling Thunder, a series of aerial attacks against North Vietnam between March 1965 and October 1968.

During the operations, the U.S. Navy and U.S. Air Force flew more than 290,000 attack sorties, dropping about 864,000 tons of bombs.

After supervising the “layaway” of the five TNT lines in1973, DuPont withdrew from the plant.

At the former VX production facility, tanks like this one were used to hold acids which were used in the production of TNT. The production took place at the Newport Chemical Depot from 1973 through 1974. Credit image: GlobalSecurity.org.

The Neighborhood Nerve Gas Plant

Newport Chemical Depot; image cropped from Military Fact Sheet, courtesy of Indiana State University

VX production plant, courtesy of Indiana State University

In 1959, the U.S. Army revamped the plant – then called the Newport Chemical Plant – at a cost of $16,498,000, to make another deadly substance, the nerve agent VX. The FMC Corporation was the construction and operating contractor; the plant continued to produce VX until 1968, when it was placed in standby.

VX disrupts the signals between the nervous and muscular systems; paralyzing muscles, including the diaphragm, resulting in most cases in death by asphyxiation.

Wikipedia notes, “VX is considered an area denial weapon … As a chemical weapon it is categorized as a weapon of mass destruction by the United Nations and is banned by the Chemical Weapons Convention of1993.”

Most of the nearby residents had heard about nerve gas, “venomous agent X,” and its deadly properties: A single drop on the skin, they’d hear, could kill a person within minutes.

At the former VX production facility, at the Newport Chemical Depot, scrubber towers were used to clean air from inside a building before the air was released. Credit for caption and image: GlobalSecurity.org.

It was also said that there were two components to this nerve gas, and the second component – which had to be mixed with the agent manufactured at the Newport plant – was being manufactured in Arkansas. That was not true. The source of that comforting piece of information is uncertain; perhaps parents concocted it to allay their children’s fears.

Sarin, another type of nerve gas, was formed by combining two toxic agents; it was manufactured in Pine Bluff, Ark.

One thousand six hundred ninety steel ton containers, called TCs, held the nerve agent VX stockpiled at the Newport Chemical Depot, as it was called at that time. These were designed for the maintenance, storage, and transportation of bulk chemical agent.

The TCs at the Newport Chemical Depot were over 6.5 half feet long, and almost 3 feet in diameter and had a capacity of 2,000 lb. The solid steel sidewalls were roughly a half inch thick, and each end was about one inch thick; an empty TC weighed 1,600 pounds. These containers were designed to withstand pressures up to 25 times greater than atmospheric pressure and internal pressures up to 500 pounds per square inch.

The tonne containers were stacked in rows three containers high, and clamped together for stability on top of wooden concave cradles inside a single warehouse of corrugated steel sheet metal supported by steel beams. Credit for caption and image: GlobalSecurity.org.

Personnel working in the storage area received training in handling the TCs and monitoring them for signs of leakage.

Munitions such as land mines, spray tanks and rockets were shipped to Newport by rail, filled with chemical agents, then shipped to U.S. Defense sites worldwide.

No Place for Chemical Weapons

In 1968, then-President Richard Nixon “halted production of all chemical weapons … and declared a moratorium on shipment in 1969, leaving the final two batches of 1,269 tons – about 5% of the country’s remaining chemical weapons – in storage in the Newport Chemical Weapons Depot.

Nearly 20 years later, on April 29, 1997, 193 nations committed to the Chemical Weapons Convention. The Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons “oversees the global endeavor to permanently and verifiably eliminate chemical weapons,” according to information on its website, https://www.opcw.org.

The Convention also “aims to eliminate an entire category of weapons of mass destruction by prohibiting the development, production, acquisition, stockpiling, retention, transfer or use of chemical weapons” by the parties to the convention.

By the numbers, OPCW says 193 nations committed to the Chemical Weapons Convention and

• 98% of the global population live under the protection of the Convention and

• 100% of the chemical weapons stockpiles declared by possessor States have been verifiably destroyed.”

As a member of OPCW, the United States stopped its production of VX in 1968 and pledged to destroy its stockpile of chemical weapons. The search was on for ways to safely destroy this deadly agent.

Information on the global security website says, “The completion of the new VX nerve agent production plant at the Newport Chemical Plant in 1961 created a need for disposal specialists at the site. A detachment of Technical Escort Unit personnel was assigned to the plant the same year.”

But when it came time to dispose of the VX and clean up the site, no good solutions were forthcoming.

Transporting VX to be destroyed elsewhere posed a risk, so it was decided that on-site destruction of the VX was the most feasible solution.

Parsons Infrastructure & Technology, Inc. was hired by the U.S. Army Chemical Materials Agency in 1999 to build the necessary structures to dispose of the VX and close the facility. More than 500 civilians were hired to destroy the 1,269 tons of liquid VX stored at the plant, named at this point the Newport Chemical Agent Disposal Facility. Nearby residents and landowners were notified of plans, meetings and potential environmental risks during the three years, 2005-08, of the process.

Cover of booklet from the U.S. Army describing the VX neutralization process at the Newport plant. Image courtesy of Indiana State University Library

Although incineration was a typical process for destroying chemical weapons, that process was not feasible for VX. Instead the VX was neutralized in steel reactors by thoroughly mixing it with heated sodium hydroxide and water. Once the neutralization was verified, the caustic wastewater, VX hydrolysate, was stored for transport and eventually incinerated by Veolia ES in Port Arthur, Texas.

This brief account glosses over the environmental concerns over the thousand-mile truck transport of the caustic wastewater, called VX hydrolysate, or VXH, from Newport to Port Arthur.

The article “A Lot of Nerve” by Randy Middleton, published in the Texas Observer in September 2007, said that both Ohio and New Jersey refused to accept the VXH.

He wrote, “In Ohio, citizen groups opposed the shipments. In New Jersey, the Army insisted the waste was safe enough to be dumped into rivers-until a study by the EPA revealed the waste could harm aquatic life. After public uproars, both states rejected the disposal plans.”

Finally, an agreement with Port Arthur and Veolia was reached, and three-truck convoys began making their way from Newport through eight states to Port Arthur. The contract for destroying the VXH was $49 million.

Opposition to the transportation and incineration of the caustic wastewater, the hydrolysate VXH, continued. Mr. Middleton wrote that whistleblowers in the Newport facility “alerted the Chemical Weapons Working Group that the waste was on the move.”

While the Army maintained that the caustic water was just that – waste water – environmentalists suggested that VX had not been wholly destroyed.

At issue was the afterlife and safety of the hydrolysate VXH. Whether it was a continual hazard or a disposable waste depended on testing the material and interpreting the results. “Could/would VX be reconstituted from VXH?” was the question.

If VX was still present, then VXH would still be considered a chemical weapon, some environmentalists argued, necessitating onsite disposal of VHX, since chemical weapons could not be transported within the United States.

Experts for environmental groups that opposed the transfer argued that the Army’s testing for VXH was insufficient. The hydrolysate was not homogenous, they said, and the Army did not thoroughly test all its components.

The last of the tonne containers of VX being shipped to Port Arthur, Tex. Photo courtesy of Indiana State University Library.

Yet, the Army, and later, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which played an oversight role, confirmed that the VX had been neutralized at Newport.

The Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons certified that the stockpile was 100 percent destroyed in September 2009.

The Army’s Historic Properties Report puts the date a year earlier: “The agent was stored in sturdy steel ton containers; there were no chemical munitions at the depot. The Newport Chemical Agent Disposal Facility (NECDF) was designed for the sole purpose of destroying the chemical agent stored at NECD. … Agent destruction operations began in May 2005 and completed in August 2008. NECDF’s permit was officially closed in January 2010.”

After more than a decade, in 2022, the CDC posted on its website, “CDC helped ensure safe destruction of over 4500 tons of nerve agent VX in the U.S. stockpile. CDC did this by reviewing facility air quality monitoring, observing demonstrations of the destruction process, and reviewing potential safety concerns.”

Closing Down

Having decided to close the plant for wartime uses and handing it over to civilian authorities, the United States Army sold much of the property it purchased, some to the original families, others to new purchasers. Of the more than 22,000 acres acquired in the 1940s, only about 7,000 acres remained to become Vermillion Rise Industrial Park.

In preparing for the handover, the Army remediated some sites, left some buildings standing and clearly designated certain areas of concern. In cooperation with the Indiana Department of Environmental Management, the Army enumerated 17 sites that that been remediated, describing their research into how each had been used and the efforts to remediate the damage to the land over its decades of wartime use.

Areas that had been deemed unfit for residential or agricultural use or use of groundwater were clearly described, and such applicable restrictions were placed on the deeds for those parcels.

Still other areas were listed as “areas of concern.” (See end note 1.) *

Having completed their efforts at environmental remediation, the U.S. Army, the U.S. Environmental Protection agency and the Indiana Department of Environmental Management in 2012 issued a Finding of Suitability to Transfer (FOST), which included information about the remediation efforts, structures left standing and areas of concern.

The FOST included “the CERCLA Notice, Covenant, and Access Provisions and other Deed Provisions and the Environmental Protection Provisions (EPPs) necessary to protect human health or the environment after such transfer.”

The FOST warned that there was asbestos and the possibility of lead paint in the remaining buildings, and they contained prohibitions against agricultural and residential uses in specified areas.

The nearly 70-page Finding of Suitability to Transfer said the intended uses for the property were industrial, agricultural and recreational.

Certain restrictions and provisions were included in the deed that transferred the property. In addition to those restrictions, there was an acknowledgement that the United States bore continuing responsibility for environmental remediation of land it had harmed.

In signing the FOST, Thomas E. Lederle, Chief of the Industrial Branch of Base Alignment and Disclosure, concluded that “all Department of Defense requirements to reach a finding of suitability to transfer have been met and all removal or remedial actions necessary to protect human health and the environment have been taken and the property is transferable under CERCLA Section 120(h) (3).”

The CERCLA Covenant provides, “Any additional remedial action found to be necessary after the date of this deed shall be conducted by the United States.”

Newport Tour Book, We made history; we made a difference

Shortly after the site was closed to military purposes, the U.S. Army Chemical Materials Agency published short history of the plant called “We Made History, We Made a Difference.”

The history concludes, “Many depot employees are from local communities and have had generations of family members and friends work on various projects during Newport’s history. With thousands of hours of training and on-hands experience, they became experts in the fields of administrative and industrial operations, including craft, utility, security and chemical occupations. The Newport work force will leave behind a legacy of safety and environmental compliance. They made history. They made a difference.”

Vermillion Rise

Vermillion Rise

A deactivation ceremony held by the Army in June 2010 signified the completion of the work needed to close the plant. The Newport Chemical Depot Reuse Authority (NeCDRA) was created to take ownership of the property and develop it for peacetime commercial and industrial uses.

When the Army pulled out, it left a shell: 108 vacant buildings, rusted street signs, a few dilapidating bunker-like structures built into berms, worn pavement and pot-holed gravel roads.

The farmland, though, is some of the best in the country, and it remains arable, in use since before the plant was created. The wooded areas of mature pine, oak, maple and walnut offer a haven for easily recognizable birds such as blue jays, robins, sparrows, hawks and cardinals, as well as scarlet tanagers and indigo buntings, which are not often seen in the grain fields.

With determination but with little in the way of finances, the Newport Chemical Deport Reuse Authority Board of Directors is working to attract businesses, ensure a safe environment for them, and protect the flora and fauna there.

Under their stewardship, the land ravaged by the manufacture of implements of war is being adapted to peacetime ventures.

Peacetime Businesses

Six businesses are now operating at The Rise, as it is now sometimes called: Scott Pet, General Machine and Saw, Newport Pallet, Gypsum Express, and Security Transport.

Eight economic development partners are working to attract businesses to Vermillion Rise: the Indiana Economic Development Corporation; Vermillion County Economic Development Council; Vermillion County Chamber of Commerce; WATCO; Duke Energy, CSX Railroad; Accelerate West Central Indiana, and WorkOne.

In addition, Oriden Power, a Mitsubishi Power venture, has plans for a 225 MWac (megawatt alternating current) solar farm in Vermillion Rise. The plan if for the solar farm to be commissioned in 2027.

The board hopes to attract agri-business, advanced manufacturing, energy and life-science entities. Several companies in these fields have already located in Indiana, and the board hopes this trend will continue for Vermillion Rise. Its website, vermillionrise.com lists several advantages of locating in the still nascent mega park: a convenient location, access to high-volume natural gas transmission lines; significant electric capacity; plentiful water; supplies of natural gas and electricity; and proximity to vocational schools, community colleges and universities

Environmental Issues

While the 2011 Finding of Suitability to Transfer states that the United States would be responsible for additional cleanups, should they arise, NeCDRA is charged with monitoring and maintaining the Environmental Restrictive Covenants.” The Vermillion Rise website provides a link to the Environmental Restrictive Covenants and Addendum, which are recorded at the Vermillion County Court House, as well as to the Phase 1 studies.

NeCDRA has taken several steps to ensure that environmental hazards have been addressed, either by remediation or by restrictive covenants.

Wildlife and Native Flora

There are plans for a recreation area, and there are protections for local endangered or threatened wildlife.

The environmental assessment noted that the area is “known to or likely to support 13 federal and state-listed protected species”: bald eagle, peregrine falcon, northern harrier, osprey, Henslow’s sparrow, sedge wren, upland sandpiper, least bittern and Virginia rail. An additional 15 species of birds, mammals, and herptiles that have been documented at the site are state-listed species of concern, and five species of vascular plants are on the state watch list. Finally, the installation has areas that support five vegetative community types that are rare, imperiled, or critically imperiled in Indiana.” No federal- or state-listed endangered or threatened plant species have been found there, however.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service showed concern for the Indiana bat, myotis-sodalis. Agricultural pesticides could harm bats if the fed on prey or drank from water contaminated by the pesticides. Management practices, such as creating buffer zones between the crop fields and adjacent forest land, were to be incorporated in to the agricultural leases to help protect these species.

Progress has been slow but continual. Reminders of the previous uses remain in the buildings, towers and berms left on the land. Memorial Chapel is gone, but the cemetery remains. Navigating the detritus of wartime activities, the Reuse Authority is working to restore and rebuild and to rework the area for 21st-century usefulness.

We made history: Image courtesy of Indiana State University Library

End Notes

Note 1. The sites and the Army/EPA recommendations to be placed on the deeds follow:

1. Night Soil Pits: Land use restrictions: excavation of buried waste in the pit area is prohibited, as is agricultural use there. … In 1968, these pits were used for disposing of decontaminated solid waste from the VX manufacturing process. The decontaminated waste included decontaminated sludge from Chemical Plant settling basin 30025. In 1977, rubble and other burned materials resulting from the razing of the RDX manufacturing facility also were disposed of in the NSPs. There is no record of when or how much “night soils” were placed in these pits. … No VX-related compounds were detected in the groundwater during the Facility-wide RFI or during earlier Site Investigation (SI) activities. … Based on these findings, the Army recommended no further action (NFA), other than implementation of land use controls (LUCs) for the NSPs.

2. Hazardous-waste Storage Building, 729A: All environmental activities completed. “The site is ready for unrestricted use.”

3. RDX Burning Ground (RDX-BG) and Old Chemical Munitions Component Detonation Area (OCMCDA): [I]t is not believed that chemical agent-contaminated M23 mines and M55 rockets were disposed of at the OCMCDA. In general, a comprehensive history is not available for the RDX-BG or OCMCDA. There is a lack of documentation on the previous site activities and the specific location at the site for activities that were conducted. … The Remedial Investigation (RI) was completed in December 1991 by Dames & Moore. … No evidence to support burial of munitions and explosives of concern (MEC) was detected. All environmental activities on the RDX-BG and OCMCDA site have been completed. These sites do not require any LUCs.

4. Gypsum Sludge Basins: These “were intended to be used to contain settled gypsum sludge produced by the neutralization of acidic wastewaters associated with TNT production in 1973/74. … The[se] areas were not remediated to levels suitable for unrestricted use. The deed will include the following land use restrictions: The GSBs area cannot be used for residential or agricultural purposes and the PCCRP cannot be used for residential purposes.”

5. Red Water Ash Basins: These RWABs were used to contain wastewater, ash, and sludges resulting from the treatment of red water associated with TNT production in 1973/74. When the TNT plant was put on layaway status in 1974, the sumps in each basin were plugged to prevent runoff to the holding sump. … Residual waste ash from the red water destruction process remains in the two southernmost basins.[2011] … The RWABs no longer contain surface water and were reclassified by EPA, Region 5, as landfill units. These SWMUs do not require LUCs. All environmental activities in the RWABs Area have been completed.

6. Present [2011] sanitary landfill: This landfill was permitted and was in operation from 1981 to 1987. Only 0.67 acre of the 30-acre site was used. “This site was closed in 1997 in accordance with Closure and Post-Closure Plans. Groundwater monitoring was to continue for 10 years after closure.” No further monitoring was necessary after 2011. “The groundwater monitoring wells have been abandoned. All environmental activities at the Sanitary Landfill have been completed.” These are the deed restrictions: “No excavation or well installation is permitted on the 0.67 acres, per the notice in the deed on the site. The site can be used in accordance with the landfill permit.”

7. TNT-Manufacturing Area Acid Area: These sites were in operation from 1971 to 1974. … There is no history of releases from these areas. … All Environmental activities at the TNT-MA have been completed. Buildings in the TNT-MA contain asbestos. … A TNT cooling tower sump where concrete was buried following clean closure of the sump is located on the site. There are no other environmental restrictions or LUCs on the area. The TNT-MA Acid Production Area can be used in accordance with the RCRA Permit for the site.”

8. Closed Sanitary Landfill (CSL): Facility operation records indicate that between 1970 and 1977, the CSL was used to dispose of nonhazardous construction debris from the TNT plant, office and shop waste with no salvage value. No records of the materials that were disposed of in this area prior to 1970 are available. …. … Although risks to future residential receptors and produce consumers were identified in the risk assessment, no further investigation or remediation is required to address human health risks based on the assumption that future land use would remain nonresidential. The CSL was not remediated to levels suitable for unrestricted use. The deed will include the following land use restrictions: LUCs will be implemented to prevent contact with groundwater, prohibit excavation of/contact with waste materials, and residential and agricultural land use.

9. Sewage Treatment Plant: The Sewage Treatment Plant (STP) is currently permitted under National Pollution Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) permit (IN 0003506) and has been in operation since the 1940s. … There is no evidence of groundwater contamination associated with the STP.

10. Demilitarization Incineration/Scrap Yard: Seeps and springs in the northwestern and southwestern portions of the SWMU produce water that is introduced into Little Raccoon Creek through surface runoff. … According to personnel reports, demilitarization/decontamination items, such as defective, empty land mines once filled with chemical agent, were decontaminated in the early 1970s using a bleach wash (3X decontamination) at another site on the installation and then transferred to the incinerator. These empty mines were heated to 5X decontamination, leaving the casings intact, and then deposited in a landfill on the installation. No records are available that indicate whether the casings were disposed of at the CSL or when operations were conducted. A 2003 personnel interview indicated that empty mine casings may have been buried onsite at the DI/SY. … The demilitarization incinerator was removed from the facility in 2004, and the majority of the area has been overgrown with native grasses. … LUCs have been implemented. The DI/SY site was not remediated to levels suitable for unrestricted use. The deed will include the following land use restrictions no soil excavation, and no residential, agricultural or groundwater use.

11. Memorial Chapel RDX Dump: It contains various types of construction debris. … [N]o further investigation or remediation was recommended … based on the assumption that future use of land for crop growing is unlikely, and LUCs would be implemented to ensure that the use of the land for agricultural purposes is prevented. The deed will include the following land use restrictions no soil excavation, and no agricultural use.”

The FOST listed four cemeteries, two fewer than the six that were enclosed in the original plant property: Carmack Cemetery, Juliet Cemetery, Walnut Hill Cemetery, Miller Cemetery and Burson Cemetery. No remediation was needed for any of these, and it appears that they were maintained until 1998. A sixth cemetery, Memorial Cemetery, appears to be somewhat maintained at present – at least grass around many of the tombstones is mowed.

12. Five Former Underground Storage Tank Sites (USTs): These were in operation from 1941 to 1990. The tanks were removed by the installation in 1990, under the oversight of IDEM. During the process of removal of the tanks, it was discovered that the tanks had leaked, thus requiring remedial action of contaminated soil and groundwater at each site. Most of the tanks had not been in use since the early 1970s, and some not since the late 1950s. … All environmental soil and groundwater remediation activities on the Removed UST sites have been completed or are in place and operating properly and successfully. There are no LUCs associated with the four former UST locations.”

13. RDX-Manufacturing Acid Facility: This facility was in operation between 1942 and 1946, and 1951 and 1957. … All environmental activities on the property have been completed and the site has been granted NFA status.

14. Basins 30007, 30008, and 30009: These basins 30007, 30008, and 30009 (SWMU-016) were located directly south of the Chemical Plant and were established circa 1950 to accept wastewater from the Heavy Water Plant. After heavy water production was halted and the facility was converted for VX production, basins 30007 and 30008 served as VX waste retention ponds. These same basins were later reutilized to accept wastewater from boiler drains and the Chemical Plant Step III cooling water system. … The basins were backfilled in the 1970s and are now covered with grass. … VX breakdown products were not detected in any of the samples from the nine borings. … The basins were not remediated to levels suitable for unrestricted use. The deed will include the following land use restrictions: no residential, agricultural or groundwater use of the site.

15. Coal Ash Basin: The Chemical Plant Coal Ash Basin was constructed in 1941 to accept coal ash from Building 401A Power House operations. The Power House operated continuously between February 1942 and September 1946 and intermittently between August 1951 and March 1957. LUCs are being implemented including no agricultural, residential, or groundwater use. The property was not remediated to levels suitable for unrestricted use. The deed will include the following land use restrictions, no agricultural, residential or groundwater use shall take place at the site.

16. Former Power House Coal Pile: This coal pile likely supported the Power House activities and was in use during the same period as the Power House (February 1942 through September 1946 and intermittently between August 1951 and March 1957). … LUCs are not required for SWMU 15 NAAP-69. All environmental investigation activities on the PHCP site have been completed and no land use restrictions are needed at the site.

17. Waste Oil Tank: The Waste Oil Tank near Building 716A is an above ground storage tank (AST). The site was in operation from the 1970s to 1993. The 1,000-gallon tank contained used oil; solvents and PCBs were introduced into the tank, and the tank was managed as a hazardous waste tank until it underwent clean-closure in 1993. … All environmental remediation activities at the Waste Oil Tank (near Building 716A) have been completed. This site is cleared for unrestricted use.

Additional areas of concern were the drainage ditch near the RDX purification process, Building 714A and Little Raccoon Creek.

Note 2

These were among the major steps taken to ensure that the environment at Vermillion Rise is safe for industrial uses. There are caveats about lead paint and asbestos, and restrictive covenants prohibit specific uses on specific parcels:

· An Environmental Assessment of the Implementation of the Base Realignment and Closure was necessary in order to comply with requirement set forth in the National Environmental Policy Act. That analysis resulted in a 2011 Finding of No Significant Impact, one that was complementary to the findings and restrictions on the deeds and in the Finding of Suitability to Transfer.

· The Reuse Authority has developed a map reflecting all the environmentally restrictive covenants on the property, as this was a cost-effective alternative to remediation; certain sites that posed no long-term threat to health or safety would require considerable cost to remediate, according to information on the Vermillion Rise website. These restrictions range from “no intrusive activity” to “no residential development.”

· The Authority commissioned two Phase I environmental studies. At 2018 study by Chicago-based Burns & McDonnell covered about 500 acres of land that had been used for farming since before the U.S. took over the property. The firm concluded that no evidence of recognized environmental conditions had been found, though there could be debris from the demolition of old farm buildings. A 2020 study by Indianapolis-based Terracon Consultants in 2020 covered about 200 acres that was “industrial, wooded, undeveloped and agricultural land.”

· The Indiana Department of Environmental Management (IDEM) signed off in a final letter in July 2109. It serves as its final decision that Vermillion Rise has fulfilled its obligations under RCRA Corrective Action Program and issued a Notice of Corrective Action Complete with Controls.

Sources Consulted

1. Historic Properties Report: Newport Army Ammunition Plant , Defense Technical Information Center (.mil); https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA175818.pdf

2. GlobalSecurity.org. https://www.globalsecurity.org/wmd/facility/newport.htm

3. “The Bomb that went off twice,” a special report to Pro Publica published on Dec. 18, 2017

https://features.propublica.org/bombs-in-our-backyard/military-pollution-rdx-bombs-holston-cornhusker/

4. https://nuclearmuseum.org/ahf/location/newport-in/

5. The Texas Observer: “A Lot of Nerve: The Army’s deadly VX waste is burning in Port Arthur,” Sept. 7, 2007 https://www.texasobserver.org › 2573-a-lot-of-nerve-th...

6. “Forging the Sword: Defense Production During the Cold War” ADA333657%20forging%20the%20sword.pdf

7. BRAC-2005_09472.pdf, DCN: 9472 NEWPORT CHEMICAL DEPOT INDIANA

8. https://www.jconline.com/story/news/special-reports/2014/03/22/ridding-newport-of-deadly-vx-nerve-agent/6738479/

9. Finding of Suitability to Transfer (FOST), Newport Chemical Depot, Category 1,2,3 and 4 parcels, Vermillion County, Indiana, February 2011 (note, title page dated March 2011)

10. https://www.opcw.org/chemical-weapons-convention.

11. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Newport_Chemical_Depot

12. Link to history of the US Army Newport Chemical Depot at https://www.dropbox.com/s/oann5b6ryk7epcl/Newport_Tour_Book_2009-02_HISTORY.pdf?dl=0

13. Link to archive created in partnership with Indiana State University at http://visions.indstate.edu/specialcollections/ncdh.html

14. Environmental Assessment of the Implementation of Base Realignment and Closure at Newport Chemical Depot, Indiana Prepared for: Newport Chemical Depot, Indiana Prepared by: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Mobile District May 2010

15. http://www.vermillionrise.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Newport_NEPA_Environmental-Assessment-EA.pdf

16. https://www.globalsecurity.org/wmd/facility/newport.htm

17. https://ahf.nuclearmuseum.org/ahf/location/newport-in/

18. https://indstate.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/ncdh/id/9/

19. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heavy_water

20. “We Made History, We Made a Difference” U.S. Army Chemical Materials Agency, www.cma.army.mil

21. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heavy_water

22. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Girdler_sulfide_process

23. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/sites/default/files/2020-02/national-ww2-museum-robotics-challenge-participant-packet-2020-updated.pdf

24. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/P-9_Project

25. https://19january2017snapshot.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2014-03/documents/ffrrofactsheet_contaminant_tnt_january2014_final.pdf

26. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_bombs_in_the_Vietnam_War

27. https://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/Visit/Museum-Exhibits/Fact-Sheets/Display/Article/195909/north-vietnam-rolling-thunder/#:~:text=OPERATION%20ROLLING%20THUNDER%3A%201965%2D1968,and%20discourage%20North%20Vietnamese%20aggression.

28. Center for Domestic Preparedness (.gov). https://cdp.dhs.gov › shared › courses › default › groups

29. http://www.vermillionrise.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Newport_NEPA_Environmental-Assessment-EA.pdf

30. http://www.vermillionrise.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Newport_NEPA_Environmental-Assessment-EA.pdf

31. Indiana State University Library